Do we still need contentious public meetings?

I drive a 2000s Vespa and randomly it falls over. It’s partly a design flaw because it fails product-market fit: the scooter doesn’t accommodate my short stature so I have an aftermarket kickstand to park it. It’s also partly (and largely) user error as I’m impatient enough to not always look for even, low sloped places to park it. Occasionally, people run into it.

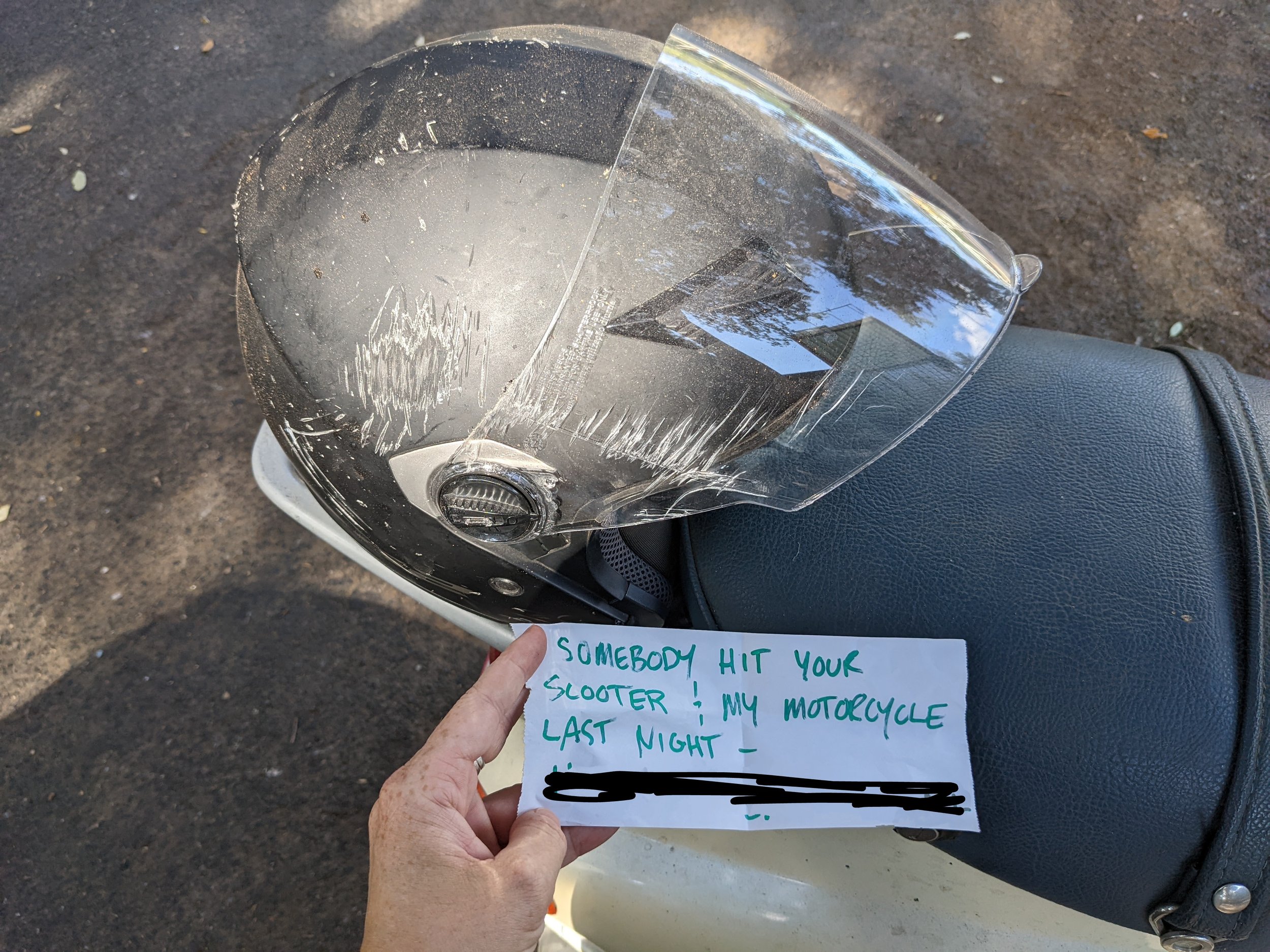

But why is not important. What is, is that when it falls over, passerby’s tend to pick it back up. There’s something about seeing a motorcycle tipped over that makes people want to flip the turtle back on its feet. Sometimes they place the helmet back on top neatly. Unhoused neighbors hang out and tell me the gory details of what happened. Once when a presumably drunk person ran into it a motorcyclist picked it back up and wrote me a little note. We exchanged emails and now follow each other on instagram (Hi!).

The tippoint point

Let’s switch gears for a moment. The region-beta paradox is the phenomenon that when something is bad, but not awful, you’re more than likely to cope with it than to change, preventing you from moving towards something better. In other words, humans continue an activity until a threshold has been reached that precipitates the need for change. A tipping point, as Malcolm Gladwell would say. Psychologically, this comes from a fear of ambiguity. (In the case of my Vespa, it hasn’t gotten bad enough for me to fix the kickstand issue.)

The idea comes from a psychologist from Harvard, Daniel Gilbert Photo cred. In this example, you’re going to walk until your threshold is hit, then you’ll consider biking even though you could have biked all along and saved all that time.

When a good Samaritan comes by and picks up my scoot, that intervention is called citizen engagement. Among a lot of other terms used in the industry. You may be doing more than you realize if you’ve ever reported a power outage or a flooded low water crossing (such as on ATXfloods). This is great because it feeds into changes they’re able to make with operational budgets, OPEX. However, I too wonder if my pothole requests aren’t being fixed because of the low income neighborhood where I live or if there’s some bigger plan in the works that makes my small request obsolete.

Obviously there are still roadblocks with this sort of engagement. The lack of clarity between how my time reporting something, and how it was taken into account, is a major barrier to people continuing to use these apps. Further, the apps aren’t easy. There’s evidently no UX designer and in the case of Austin it is organized by department, not by infrastructure asset type, which makes no sense to someone looking to report. A search bar function would be an easy add.

Further, while important to get things tagged and fixed, I personally think it’s more effective to engage on the capital expenditure side, CAPEX. It’s less of a bandaid fix, addresses the root cause, and orients the infrastructure budgets around your long-term goals, not your current-day pains. Let me explain.

From past to present

We’ve known that we need to solicit public feedback for decades. Community input helps to ensure we don’t carelessly or misguidedly design in a way that is racist or classist. We actually have hardcoded this into the design process, meant to bring in community information before we make changes that affect the community. If you’re in for a good podcast, here’s one on Boston’s Big Dig that illustrates how people can make an impactful difference, and why when they’re not involved, we end up with solutions that can be inequitable. It, like the article I’ll mention below, chronicles the changes in how we view big government and infrastructure planning.

The process for community feedback that you see made fun of on television is mid-design, pre-build. The technical analysis has been completed by experts, the financial analysis has been iteratively redone, and then they begin the social analysis once they have design options to present. But research shows that the people going to these meetings are all one privileged demographic: the white people with time, money, and opinions. Oftentimes loudly and disrespectfully….hence the satire.

One of my friends sent me this Vice article which points out the failures of the current system for public input - how it makes people feel less heard and how it slows down the infrastructure development process that in turn just makes people less trusting turning it into a vicious cycle. It’s worth a read if you’ve ever been curious about some of the truly bizarre things that happen at public comment meetings. I used to work with a woman who’d told me that in the 90s she had gotten death threats for trying to give out rebates for low flow toilets. Ah, the 90s. Crop tops and casual racism.

“The Midwest planner said for each meeting that takes between six and 12 staff members and hundreds of person-hours of work, they perhaps get one or two useful comments. ”

Now, from a combination of moving further to the right (bizarre public comment meetings, with action items that add tens of thousands of dollars onto the project, AND increased costs for meetings just to combat lawsuits) and the threshold pushing to the left (more technology to submit comments, ideas, and complaints), we now find ourselves in a beta-region environment. Things have gotten bad enough that it has stimulated change.

participatory planning is key

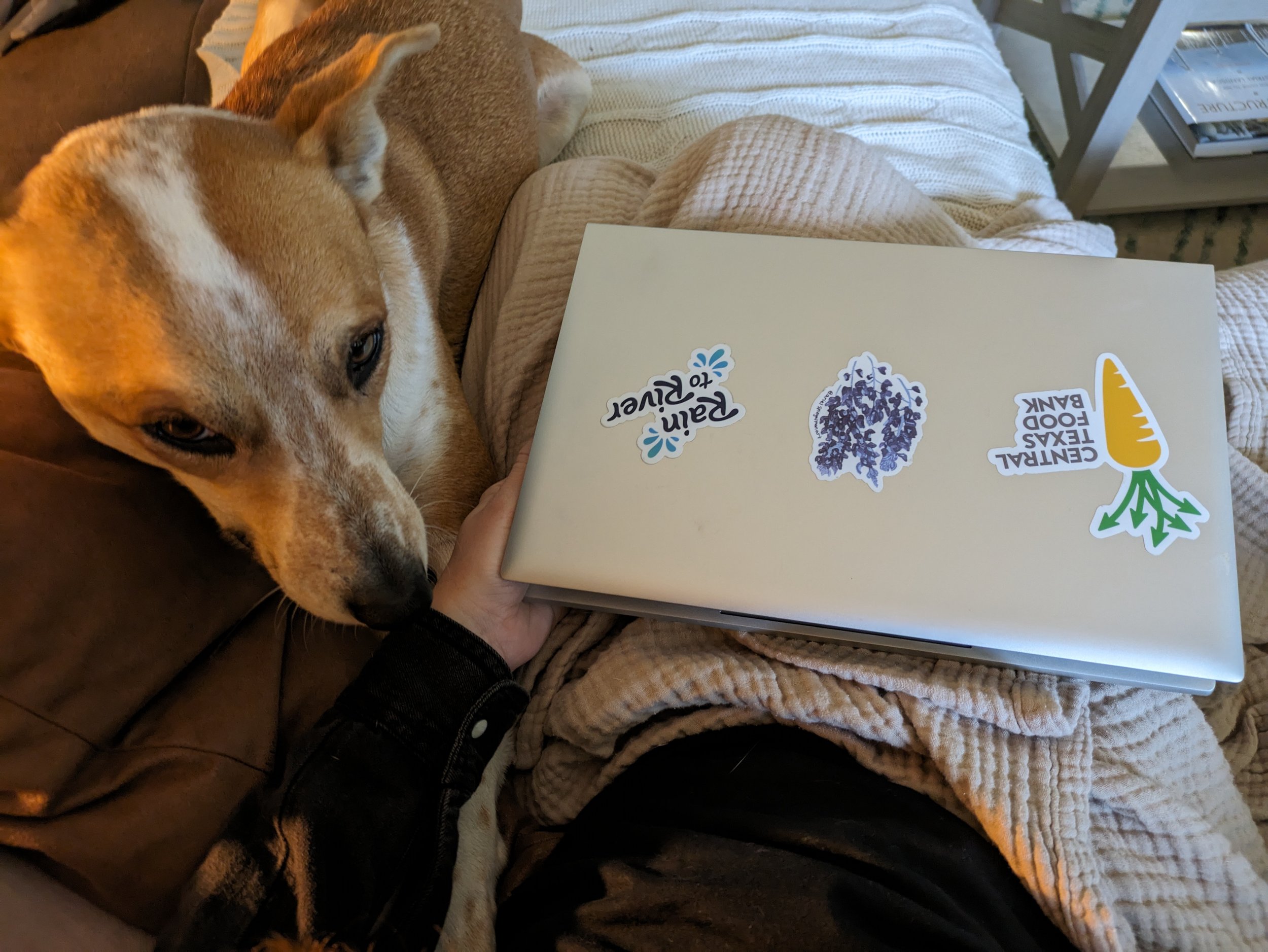

It’s possible to get community feedback pre-design, pre-build. Rain to river is our local ATX portal to put ideas, in addition to problem areas, for things that you want improved about the watershed. The idea is that when the Watershed Protection department (which is a function of the local water utility) goes to plan for capital investments they can use the information provided to shape their goals. I emphasize this part of the intent because shaping goals works better than taking in any individual, biased opinion which is what we get from community feedback meetings.

This input is known as participatory planning. In addition to systems like Rain to River, we can pull planning insights out of the OPEX systems if we can reduce the barriers I mentioned above. With a meta analysis (AI use case / large language model anyone?) to understand which of those comments would be ameliorated through better design.

It doesn’t have to be hi-fidelity. I’ve seen quite a few utilities use Facebook/Meta to post plans and get community input. It also gives market data to say what’s most important to most people (by seeing what others upvote). Instead of just opinions, a meta analysis provides data about opinions that can help to alleviate biases in design.

Community feedback process is changing

Technology is changing the way we-the-people interact with utilities. Take this story of a wastewater treatment plant that found a wedding ring when they cleaned out the basin 13 years later and was able to miraculously find its owner. Thanks to my colleague for forwarding on that story, with his comment about how often they should be cleaning those basins.

I know that after seeing all the memes on the horrors of public feedback meetings, people may feel like the process is broken. However, technology can be used on the mid-design side more effectively, too. People who wouldn’t have the confidence or time to stand in front of a room on a microphone can use their web browser at home to view the alignment (e.g. rail, bike lanes, etc) and see the impact of a proposed design such as they did for a 5 mile tunnel in the City of Gothenberg, Sweden. I love that a lot of the public comment meetings have moved over to Zoom; you don’t have to find transportation to get to the meeting whose objective is to discuss the poor transportation.

This design on South Congress always makes me giggle - if you do pull up to the white stopping line in the bike lanes, you’ll be blocking the bike lane headed in the other direction. Things like this are hard to see on specs and CAD drawings but in a 3D model you’d get a better sense for how the design functions. Or maybe an actual cyclist could remind them how big bikes are during the mid-design feedback?

By using technology, we can build the foundation of equitable design but we need your help. Take the time and put in feedback for new ideas. Tag problem areas even if you know they’ve been reported by others. And thank your city engineers at the public comment meetings - its certainly not a job I have the patience for.

What if your city doesn’t have these sorts of feedback systems yet? Tell them they should. After all, we’re in the region-beta environment. Better yet, ask for a digital twin that can help to preserve continuity of design goals from planning through to design, construction, and O&M. For technology-curious readers, here’s an interview with ChatGPT pretending to be a credentialled water expert that does a pretty great job explaining it all!

One of the things that makes me really excited is using technology to build the foundation of equitable design, which I’ve discussed in A Failure of Power and Essential Infrastructure People. Technology-enabled planning allows us to hear more ideas more empathetically and boil down the ideas to have designs that best work for a diverse city with diverse opinions. In a respectful way.

It’s still not without faults: the form builders need to be user friendly, AI needs to remove bias, and the designers need to implement the information gathered. And of course, we need to undo some of our laws that codified the bulky process that requires public input periods on all projects. But it takes us forward.

Next time you see me at a coffee shop, you’ll know what my Rain to River laptop sticker is all about. Thanks for picking up my scoot on the way in.

A rainy Pride parade

Listening: Aimee Carty’s Not Good at Parking

Reading: That vice article. My favorite cynical quote, and what you’d expect from Vice, “Random people from the community who haven’t even looked at your proposal will demand you study some new routing that you, a person with a master’s degree on the subject, know is nonsensical by any conceivable measure. You will have to study it so you can tell the judge you studied it. You will then have to respond to that person in writing, without using any mean words. Each of these additional studies will cost tens if not hundreds of thousands of taxpayer dollars and add months to the project. Those same cost overruns will be decried by the very people who showed up to the meetings demanding you do those studies as evidence you’re incompetent and shouldn’t be allowed to build anything in the future with their hard-earned taxpayer dollars.“

Working: Dam Monitoring solution business plan / yearly strategy session